According to democratic socialist Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the Covid-19 pandemic is proving that the United States “is a brutal, barbarian society for the vast majority of working-class Americans.” As evidence of this, she claims that “40% of us couldn’t even afford a $400 emergency” before this crisis, and Covid-19 “is more than a $400 emergency.”

However, her “40%–$400” statistic is false, and the facts that broadly inform this issue reveal that:

AOC’s Allegations

In a recent video, Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D–NY) declared: “This is supposed to be the richest society in the world, and I think what this crisis is showing us is that this is only a rich society for a very small amount of people, and it is a brutal, barbarian society for the vast majority of working-class Americans because 40% of us couldn’t even afford a $400 emergency before this thing started. This is more than a $400 emergency, and we’re really going to have to step up and completely change our approach to our public systems.”

The “40%–$400” Statistic

The statistic cited by AOC stems from an annual Federal Reserve study of people’s “self-reported ability to handle unexpected expenses.” Contrary to her claim that “40% of us couldn’t even afford a $400 emergency,” the survey actually finds that 12% of U.S. residents fall into that category. Furthermore, the facts surrounding this 12% figure reveal that it overstates the portion of people who can’t afford such an expense.

Per the Federal Reserve’s report on this issue, “if faced with an unexpected expense of $400”:

Hence, AOC’s figure of “40%” includes people who would place the expense on a credit card and not pay it off right away. This is materially different from her claim that they “couldn’t even afford” it.

Moreover, the same report notes that another survey found 76% “of households had $400 in liquid assets (even after taking monthly expenses into account).” In other words, it’s not that they “couldn’t” immediately pay for an unexpected $400 expense; they just preferred not to do so. Given that 40% of U.S. residents carry a credit card balance “most or all of the time,” the “$40%–$400” statistic says little beyond that.

With regard to the 12% who claim they “would not be able to cover the expense at all,” consumer data shows that the lowest-spending 10% of U.S. households spend an average of $1,369 per year on entertainment and $208 per year on alcohol. That’s enough to handle about four $400 emergencies every year. Furthermore, these figures are based on household surveys, and the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis explains that they “are subject to deliberate underreporting of certain items.”

The fourth-lowest 10% of households—who are also included in AOC’s 40% figure—spend an average of $2,830 per year on entertainment and $320 on alcohol. This is enough to cover about eight $400 emergencies, which means the issue is not about a lack of money but how it is spent.

In spite of these facts, media outlets have published headlines like these:

Also, the survey includes all “noninstitutionalized, civilian” adults who live in the U.S., not just “working-class Americans” as AOC asserts. Thus, it also includes non-working Americans and millions of unauthorized immigrants who are not legally allowed to earn income in the United States. Since these individuals often work off the books and don’t disclose the money, this potentially skews the results of such surveys.

Government Social Programs

Also belying AOC’s rhetoric about the inability of Americans to weather a Covid-19 crisis is the fact that taxpayers already pay for most of the living expenses of low-income households, including the vast bulk of their medical costs. Roughly 22% of the U.S. population is on Medicaid, and as the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services explains:

Beneficiary cost sharing, such as deductibles or co-payments, and beneficiary premiums are very limited in Medicaid and do not represent a significant share of the total cost of health care goods and services for Medicaid enrollees.

Beyond medical care, federal, state, and local governments provide a wide range of other benefits to low-income households. In 2015, the U.S. Government Accountability Office identified 82 federal means-tested welfare programs. When all of these benefits and other sources of income are included, U.S. households that are officially “in poverty” consume an average of more than $50,000 per year in goods and services. This amounts to 5.2 times the income they report to the Census Bureau.

Governments also shift the costs of some welfare policies to the private sector. A prime example is the federal law that requires most hospitals with emergency departments to provide an “examination” and “stabilizing treatment” for anyone who comes to such a facility and requests care for an emergency medical condition or childbirth—regardless of their ability to pay and immigration status.

In 2018, federal, state, and local governments provided an average of $23,050 in social benefits to every household in the United States. The federal government defines these as “payments from social insurance funds, such as social security and Medicare, and payments providing other income support, such as Medicaid and food stamp benefits.” These alone are on par with the total average household income of Eastern Europe, including both private earnings and government benefits.

In addition, the federal government has recently enacted enough Covid-19-related legislation to nearly double its regular $2.6 trillion annual spending on social benefits. This includes but is not limited to $192 billion for the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and an estimated $2.2 trillion for the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act.

Impact on Personal Savings

Such levels of government social spending, which AOC wants to increase, are the main reason why many workers don’t save more of their income. As detailed in 2016 working paper published by the European Central Bank:

Furthermore, Americans must ultimately fund these programs, which hinders their ability to save. The $23,050 per household in social benefits that governments paid out in 2018 ultimately came from American households. Although high-income households bear a greater share of these costs than others, middle-income workers lose about 15.3% of their paychecks to social insurance taxes.

If, in contrast, these workers could have saved and invested a fifth of these taxes during their careers, each retired middle-income worker would have an additional $199,000 to $764,000 in savings today.

Voluntary Charity

Long before governments began providing appreciable amounts of social benefits, the U.S. led the world in charity, and it continues to do so.

In notes that Thomas Jefferson wrote in the 1780s, he described how Americans cared for the sick and poor with striking contrast to modern, government-run welfare programs:

In the 1830s, a French historian and political scientist named Alexis de Tocqueville visited the U.S. and wrote a famous work entitled Democracy in America. In it, he stated that what “I most admire in America” is how people were personally engaged in advancing the welfare of society:

In the United States the interests of the country are everywhere kept in view; they are an object of solicitude [concern] to the people of the whole Union, and every citizen is as warmly attached to them as if they were his own.

When a private individual meditates an undertaking, however directly connected it may be with the welfare of society, he never thinks of soliciting the cooperation of the Government; but he publishes his plan, offers to execute it himself, courts the assistance of other individuals, and struggles manfully against all obstacles. Undoubtedly he is often less successful than the State might have been in his position; but in the end, the sum of these private undertakings far exceeds all that the Government could have done.

Although federal, state, and local governments consume about 33.5% of the U.S. economy—at an average cost of $54,000 per year to every household in the nation—U.S. citizens still donate about $50 billion each year to charities that provide “direct services to people in need.” That equals an average of $1,316 for every person who is reportedly below the poverty line.

U.S. citizens also donate $38 billion per year to health charities, along with $59 billion to education charities, and $127 billion to religious groups, many of which serve the poor.

A 2016 study of 24 nations by the Charities Aid Foundation found that the people of the United States are most generous and donate 1.44% of the nation’s gross domestic product to charities. The next closest nation, New Zealand, donates 0.79%, or 45% less than the USA. Nations such as Finland (0.13%) and France (0.11%) donate less than one-tenth of the USA.

The Big Picture

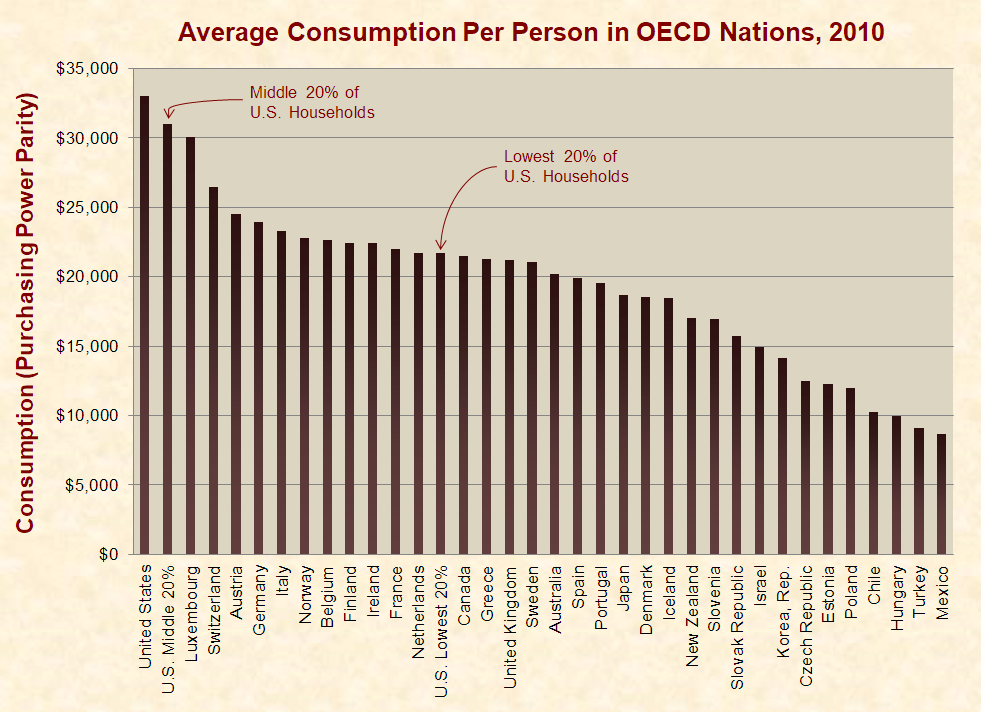

The most comprehensive mass measure of people’s financial condition is their consumption of goods and services. This is the World Bank’s “preferred” indicator of material well-being due to “practical reasons of reliability and because consumption is thought to better capture long-run welfare levels than current income.”

The latest available data show that middle-income Americans and even the poorest 20% of Americans consume more goods and services than the national averages for all people in most affluent countries. This includes the majority of nations in the prestigious Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, including more socialistic nations that AOC says the U.S. should emulate:

An important strength of this data is that it is adjusted for purchasing power to measure tangible realities like square feet of living area, foods, smartphones, etc. This removes the confounding effects of factors like inflation and exchange rates. Thus, an apple in one nation is counted the same as an apple in another.

Summary

Contrary to AOC’s portrayal of the USA as “a brutal, barbarian society for the vast majority of working-class Americans,” the key facts that inform this matter show that:

James D. Agresti is the president of Just Facts, a think tank dedicated to publishing rigorously documented facts about public policy issues.